As I read through the 13 responses (Vince Aletti, George Baker, Walead Beshty, Jennifer Blessing, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Geoff Dyer, Peter Galassi, Trevor Pglen, Blake Stimson, Charlotte Cotton, Corey Keller, Douglas Nickel, and Joel Snyder) for this symposium, I noticed a few things overall.

- The need to define exactly what "photography" is and exactly what "over" means was a prominent concern.

- This discussion seemed for some people to be a catalyst into topics that they have wanted to verbally express, but have not yet found the time and/or place to do so. These responses seemed to sort of maybe start out relating to the question, then veered off course and never really returned to the question, nor did they ever give an answer one way or the other.

- There is no actual answer to this question.

DiCorcia draws up a standpoint that photography isn't quite over, but that's not the right question. He agrees, like most, that photography's form is rapidly changing (and how can it not in this digital age?), but he also adds that the content has stayed the same. Altered form, same old content. Photography has lost its grip on reality, and is not now measured by how true the picture is, but how much of a lie it is not. DiCorcia also relates photography's "overness" in terms of its stance in the art world. He states that art has been irrelevant in the world, but that photography has been quite relevant (even though photography has tried so hard to be an art and is now widely accepted as art...sort of), and now that photography is "tired-out", maybe it is either bringing the art world with it, or being liberated from it.

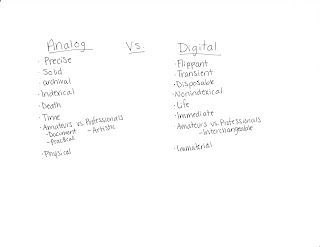

What I found I connected to in diCorcia's response was his statement on the change of form but not content. Maybe that's what defines a medium though? The form? But photography's content is in a way its form because no other medium can capture its content in the same way. Photography's form is a view of reality in the most documentary sense of the word, and its content is just what we choose to frame as reality. So the tools that we are using to form its, well, form, and content also, has gone from chemicals to electronic transmission through a screen. I can still photograph a tree with both digital and analog means and you will still see both as accurate representations of that tree (unless of course I change the digital image to have tentacles protruding from said tree, but that's a different topic).

Geoff Dyer started out by describing both jazz and painting and the ways in which they have risen, climaxed, and subsequently changed (but thrived). He also mentions elegies being written for these different art forms after the climax, but says that he has not been able to find these elegies in photography regardless of its many climaxes and falls. Photographic movements (and here I am referring to movements as the people who started them as well as the actual movement in the medium) have exploded and then sort of quietly slipped away. There is no mourning, we just keep moving forward. We'll study these people and these movements, but they will become nothing more to us than an inspiration, perhaps, or maybe just a useful bit of information tucked away until we need it someday.

Dyer's point on multiple climaxes in a movement or medium is what I connected to. There will be phases in a medium that will move through time like a wave frequency, rising and falling, each with a crest and a trough, followed by another crest and trough, but the medium will remain widely unchanged. Photography will still be photography at the end of the day, whether Eggleston made his godawful (yet somehow revered) photographs or not.

Joel Snyder's response to this question seemed the most unique of them all. Whereas most people toyed with the idea that 'well, photography isn't necessarily over, but it's not quite the same, but it's sort of on its way to being over...', Snyder started his essay out with saying that "Photography...is more vital than it has ever been." He agrees that it is ever changing and that some of the chemical/analog processes are slowly shrinking, but says that they will never disappear, just as all the old photographic processes are still used to some extent today. He also points out that digital photography is growing exponentially every day. With more and more people gaining access to photographic equipment of some kind (cell phones, point and shoots, disposable cameras, etc), there is no end in sight for the viral medium. However. Snyder does make it clear that although the use of photography is growing, the interest in it is shrinking. It is not so much used as an art form any more as it is more so used now as the growth of our third arm.We photograph our food at restaurants, we photograph our kids blowing out candles and opening presents, we photograph college students playing beer pong, we photograph sexual acts, we photograph sweet bruises we get and post them online so we can tell people what happened. We aren't usually consciously thinking "Wow I'm using photography right now" when we snap the shutter, we just want to document the moment and this is how we do it. The difference with photography vs. other art forms, is that photography has become part of our daily lives. We wouldn't sit at the table and say "Okay, son, now I need you to start opening that present, yup, just like that, okay....STOP. Freeze, just like that. Don't move" and then paint the scene. Nobody does that. But if they did, they would be thinking about painting as they painted. John Doe is not thinking about photography as he's photographing his kid open the present that he's wanted for months. He's just not.

So according to Snyder, photography as an art form has become the minority. Photography as photography, however, has become a practicality. In this way, photography is surely thriving.

To sum it up, I would say that my ultimate answer to this question, sort of in combination of these three responses would be as follows:

Photography is not dead, photography is changed. Some aspects of photography in relation to its use in the art world may be over (or close to over), but in the form of he digital, photography has become a definition in all of our lives. We use it daily, we communicate with it, we share it. This digital age of photography is still rising, but eventually it will climax, just as analog did. At that point, it will fall, and a new rise in the medium will begin. With photography being used so widely, it has branched from the art world. The public probably does not see it as art so much, because it already proved itself to be that. It wasn't art, then it was, and now it has morphed into something that is accessible to everyone (people go to museums to see the paintings of the masters. They cannot ever do that. Photography seems a bit...easier, regardless of how easy it actually is. People would consider themselves photographers long before they would consider themselves artists.) Photography as we knew it yesterday is over, and photography as we know it today is in the process of becoming over, and photography as we will know it tomorrow is about to be over. It is always changing and always reforming. As things (ideas, movements) are put into action in photography, they are constantly becoming part of photography's history. Ansel Adam's f64 movement is over. Street photography as it was in the middle of the 20th century is over. Black and white photography is over. Color photography is over. Parts of these larger ideas are still used in the everyday photograph, but they are no longer part of a larger movement. They stand alone.

P.S. I've thought all morning about this idea of photography being art (because a lot of these responses dealt with photography either breaking from art or having been art, or how the art side of photography is dead, etc) and I actually am now wondering if photography ever could have been art. It seems as if taking something that existed in life (maybe even a piece of art itself) and putting it into the spacial frame of a photographic lens, then transferring something palpable into a 2D representation on a piece of un-unique paper that has mass produced thousands of other once real life things, is nothing more than creating relationships. I photograph food. The art of this process for me is in the creation of the food, the styling of the food, and how to make it look good in "real life" before the camera is even set up. I know how to frame it to make it look aesthetically pleasing, but is that part of the art of photography? Or is that simply part of knowing what aesthetic beauty looks like when put into a geometric frame. Photography would change drastically if photographs were circular. Or triangular. I guess it's a set of skills that need to be learned to understand what a good image would look like in a photographic frame, and actually using the camera to change exposure and focus and all of the technical aspects would be part of a skillset of the medium, but I'm still not convinced that this can be considered art. It seems to become more artistic when it is manipulated, and people argue in this case that at this point, it may not be photography anymore because it has lost its realistic representation. But what am I creating besides a frame? This doesn't really have to do with this blog post, but it's been on my mind this morning.